Currently reading

Doomsday Book

Psychotic Reactions and Carburetor Dung

Book of Shadows

Wastelands: Stories of the Apocalypse

For the Win

Zone One: A Novel

Well, well, well. I was expecting this book to be tiresome, but it was a page turner. Not too shabby, and my first Thomas Mann read. Now to reread it in German...

Well, well, well. I was expecting this book to be tiresome, but it was a page turner. Not too shabby, and my first Thomas Mann read. Now to reread it in German...

This review was originally published on Click Clack Gorilla.

This review was originally published on Click Clack Gorilla.You want it in a nutshell, here it is. This book is fun to read. High cheese factor, shallow plastic characters, and hugely problematic depiction of women and anyone who isn’t white, but page turning.

But maybe you won’t think its cheesy. Maybe you like electricity so much that you’d be swept up in the calls to “Give my children the lightning,” by the images of a hero on his death bed croaking about how important “the lightning” is before biting it in a dramatic public scene. Ummm, “the lightning”? What a romantic way to think of electricity. Which brings me to the crux of this book: defending industrial civilization. But let me back up.

Lucifer’s Hammer is a big fucking comet, and it hits earth. Earthquakes and tsunamis and hurricanes and floods destroy most of civilization. A lot of people die, food is scarce, people start eating people—you know, the familiar backdrop and props of post-apocalyptic fiction. We follow an almost George-Martinian number of characters as they flee from cities, looking for a safe place to bunker down, and most of them end up on Senator Jellison’s Ranch where a large group has organized in hopes of surviving the winter.

Meanwhile, a group that I thought of as Cannibals for Jesus believe that they have been called to complete God’s work and destroy the small pockets of civilization that have come through the crisis. They attack the ranch, and then go after a nearby nuclear power plant that is, miraculously, still running. And the people say, hark! What devils are these that would dare attack the sacred nuclear power plant! We shall band together, though it may mean the death of us all, to fight for the right to nuclear power! Not only does Niven make nuclear power detractors (and environmentalists) completely unsympathetic, devilish lunatics, he makes sure to mention that even the hippies on the local commune change their back-to-the-earth tune once faced with the realities of a truly off-grid existence. “Let me tell you, it doesn’t work,” says one ex-hippie character of the commune life. Wa-waaah.

“It’s too much, don’t you see that?” Owen demanded. “Atomic power makes people think you can solve problems with technology. Bigger and bigger. More quick fixes. You have the power so you use it and soon you need more and then you’re ripping ten billion tons a year of coal out of the earth. Pollution. Cities so big they rot in the center. Ghettos. Don’t you see? Atomic power makes it easy to live out of balance with nature. For a while. Until finally you can’t get back in balance. The Hammer gave us a chance to go back to living the way we were evolved to live, to be kind to the Earth.”

It sounds reasonable doesn’t it? I happen to agree. But I’d bet that Larry Niven doesn’t, as he has one of the madmen Cannibals for Jesus saying it to ring in their unholy war on technology. What the sympathetically portrayed characters say is, “Give us that electricity plant and twenty years and we’ll be in space again.” Because the most important thing to consider when fighting for survival is getting the space program started again. Religious zealotry and mania aside, I bet you can guess which side I thought the real lunatics were.

a feminist reading

And as for you, ladies, you’re just going to love living in the world of Lucifer’s Hammer. There’s a lot of rape, and then, get this (says a largely respected and sympathetic character):

"The only good thing about Hammerfall, women’s lib was dead milliseconds after Hammerstrike."

Wow, I’M SO GLAD. That pesky women’s lib. Umm? Later a female character says: “It’s a man’s world now…So I guess I’ll just have to marry an important one.” This book is a total feminist fail. There are a number of female characters (though we only ever hear about the beautiful ones, and the women are always described in terms of beauty whereas the men are not), though what we see them doing most is having sex. A few of them manage some heroics, but we never get to see this world through their eyes.

The only female perspective Niven gives us is Maureen, a beautiful (duh) woman who is thrust into the role of prize princess in the new group. She battles with depression, particularly when she realizes that she is the trophy whose possession will determine the next ruler of the ranch once her father, the Senator, passes. She is unhappy about it, but her criticism is fleeting and in the end she picks a mate and dons the new throne without complaint. And did I mention the couple who didn’t get married before Hammerfall because the lady wanted to focus on her career? But who get married and start having babies as soon as the world ends? At the end of the story, it seems, marriage is a woman’s highest priority in this new, nuclear-powered world. How very civilized.

and as for the characters who aren’t white

The place Niven gives blacks (he doesn’t mention any other non-white races) is strange and baffling. Some professional thieves (all black) survive and rape and pillage and join the Cannibals for Jesus. There are a few sympathetic black characters, but racism is everywhere in the new world, as if everyone had been waiting for a disaster to allow them to really get down with their racist selves. Sheesh, Niven, just because you published this in 1977 doesn’t mean you get to be an asshole. Minus twenty thousand points. Worse are the reviewers all over the internet who chalk this up to “1970s politics.” So Niven’s racism is ok to ignore because everybody was doing it in the 70s? Umm, right.

read it or burn it?

Despite Lucifer’s Hammer’s many failings, I enjoyed reading it. The post-civ scenario is one I haven’t read before, as is the look into a mind very different than my own. It is pop-y and cheesy and totally ridiculous over and over again, but I enjoyed spending time between the pages and the title would make a great name for a metal band. But a fun read does not a good book make, and if you were to use its pages to start your wood stove, I would totally understand.

Blindness had been on my post-apocalyptic to-read list for months, but a chance encounter at a local bookstore and the chance discovery of a book club—set to read Blindness that very week—put it on my fast track. I bought the book, and I spent three days in its nightmarish, reeking, broken world. I went with the first to contract the white blindness into the mental institution where the government sets up a quarantine, shuddered as the bathroom became an open sewer, hungered with them as the government failed to deliver appropriate rations, mourned when the frightened soldiers guarding them itched their triggers. It is only because of the presence of a single seeing woman that the group eventually thrives. Or what passes as thriving under the circumstances.

Blindness had been on my post-apocalyptic to-read list for months, but a chance encounter at a local bookstore and the chance discovery of a book club—set to read Blindness that very week—put it on my fast track. I bought the book, and I spent three days in its nightmarish, reeking, broken world. I went with the first to contract the white blindness into the mental institution where the government sets up a quarantine, shuddered as the bathroom became an open sewer, hungered with them as the government failed to deliver appropriate rations, mourned when the frightened soldiers guarding them itched their triggers. It is only because of the presence of a single seeing woman that the group eventually thrives. Or what passes as thriving under the circumstances.The dialogue, which I had heard ruined the book for a number of readers on many online reviews, is written in a flowing style without he saids or she saids. (“It cannot be, They’ve taken away our food, The Thieves, A disgrace, the blind against the blind, I never thought I’d live to see anything like this, Let’s go and complain…”) Though I can understand how this might trip a body up, how better to immerse the reader into the story, how better to make the reader as uncertain as the blind characters about who is talking? A stroke of genius on the part of Saramago. When an artist is able to make style support content on that level I just die. Good job, Jose.

But there was an aspect of Saramago’s story that bothered me as I read, more than the conditions in which the government left the quarantined to suffer, more than the state of the restrooms, more than the power plays and violence, and it was at the base of everything the book was saying. Blindness as metaphor. Blindness as floodgate for the worst of humanity. Sight as the thread that held civilization together. Sight as enlightenment. Sight as knowledge. How would a blind person feel reading this? How did I feel about the implication? Though the book is expertly crafted, using a real-life disability as a metaphor is deeply problematic.

I followed this feeling onto google, looking for blind reader’s reactions to Saramago’s tale and came across an essay written by Liat Ben-Moshe—an academic from the field of disabled studies. Though he initially was quite taken with the novel, he later became very critical of what its use of a disability as such a negatively weighted metaphor was conveying to readers, and particularly critical of how he had been teaching the text to students. The article gets to the heart of what nagged me from Saramago’s page so articulately, that he might as well tell you himself:

Saramago’s depiction of blindness is that of a sighted man who views blindness as a radical departure from his own corporeal being. Different experiences of living in the world are never explored. Blindness is conveniently used the way Saramago assumes most people conceive of it and yet remains invisible.

Blindness does not just represent a radical form of Otherness, but operates as a sign to refer to limitation, lack. Throughout the novel, blindness is shown to lead to disorientation, chaos, and lack of familiarity with space and time. …

A more critical read, however, yields a different analysis. In this view, society fails to function not because of people’s blindness, but because the government is not able to provide the ordinary services that citizens are routinely dependent upon for survival: the production and distribution of food, water, and electricity; the maintenance of the infrastructure of transportation and communication; and so on. However, in the novel, as in daily life, dependence is projected onto the people who are perceived as embodying it on a daily basis, that is, people with disabilities. …

It is not surprising perhaps, since Saramago seems to use blindness only to tell another story, one about the human condition in general. But again, why choose blindness? Saramago’s parable, like so many other literary and cinematic depictions, seems to equate blindness with lack of knowledge. The analogy between “seeing” and “understanding” is one of the oldest ideas in Western philosophy. …

Blindness, like all disabilities, is also normatively viewed as a personal tragedy, something inflicted on the individual, a condition that a person suffers from. This narrative is closely related to a medical narrative claiming treatment and cure. Blindness should not be embraced and experienced as an identity, equal to any other, but should be pitied and/or treated.

Ben-Moshe goes on at length on the subject, and I highly recommend reading his article yourself. If you haven’t got the time for in-depth articles, I will sum it up for you in one sentence: Saramago uses blindness as a metaphor without a single hint of critical thought and with all the negatively loaded tropes common in non-disabled representations of the disabled. This work makes it clear that he is a talented writer capable of nuance and depth, and yet at the end of the novel, at the end of the day, we have a writer dealing in tropes, in a centuries-old, problematic metaphor. At the same time, Saramago’s use of blindness as the x-factor in this world is also a fascinating study, and I don’t wish he’d written a different book with a different disability. Authors are not bound to write only politically correct, “clean” texts, and I think the world is more interesting for the discussion that an issue like this in a text of this quality can create. The responsibility here lies with us as readers, in the way we engage with the text, what we choose to discuss and what we choose to ignore.

Read the rest of this review here: http://www.clickclackgorilla.com/2013/03/25/blindness-by-jose-saramago/

It took me seven years to finish reading this book. It is not that it is not magnificent--it is. But it lacks story or any driving force to help propell the reader to the end. The writing is gorgeous, masterful, but reading it often felt like wading through thick mud. I am glad to be finished with it, and will enjoy returning to it to reread the passages I found particularly beautiful, but I doubt I will ever read it again. It is Pessoa's own character, or I should say characters as he invented so many versions of himself to write with, that interests me the most.

It took me seven years to finish reading this book. It is not that it is not magnificent--it is. But it lacks story or any driving force to help propell the reader to the end. The writing is gorgeous, masterful, but reading it often felt like wading through thick mud. I am glad to be finished with it, and will enjoy returning to it to reread the passages I found particularly beautiful, but I doubt I will ever read it again. It is Pessoa's own character, or I should say characters as he invented so many versions of himself to write with, that interests me the most.

Far from the best in the series. I suspect Stirling was looking forward to describing what happens after this book, and just rushed through the events of this. In part enjoyable, but so far the most terious in the series. Fingers crossed that The Tears of the Sun is better...

Far from the best in the series. I suspect Stirling was looking forward to describing what happens after this book, and just rushed through the events of this. In part enjoyable, but so far the most terious in the series. Fingers crossed that The Tears of the Sun is better...

Three times a charm. And how. My third e-book reading experiment was to read Ten Thousand Miles by Freight Train by Carrot Quinn who I'd known through her blog and mutual friends for years, but have never met. She's an excellent writer of the Annie Dillard school, and her prose has come a long way since she first started telling her train hopping tales on the internets. Her recent post about How to Be Poor is the most wonderful thing I've read on the subject in a long, long time. (Maybe ever? My memory is not whole enough to say for sure. If you are thinking about quitting your job, this is on the syllabus.)

Three times a charm. And how. My third e-book reading experiment was to read Ten Thousand Miles by Freight Train by Carrot Quinn who I'd known through her blog and mutual friends for years, but have never met. She's an excellent writer of the Annie Dillard school, and her prose has come a long way since she first started telling her train hopping tales on the internets. Her recent post about How to Be Poor is the most wonderful thing I've read on the subject in a long, long time. (Maybe ever? My memory is not whole enough to say for sure. If you are thinking about quitting your job, this is on the syllabus.)The main downside to e-booking so far, has come at review time. I enjoy reading on my phone. I enjoy the convenience of always having a couple of books with me, but I haven't gotten the hang of marking passages yet. This, in combination with the format, means that, come review time, I can't sit down to thumb through it again, letting my eyes find passages of interest a second time, helping me sum up the experience in words. Scrolling just doesn't do it for me, and my eyes are less likely to stick somewhere relevant on a screen. But! The find feature! Because of the find feature I can share my favorite metaphor—and Carrot is quite good with metaphors—in the entire book, can give you a tasty little morsel to get you ready for a delectable meal.

Carrot is describing hitch hiking, and the way that the people who pick you up tend to spill their life stories. Why do they do this? "Talking to you is like stuffing a note into a bottle and tossing it into the sea." Brilliant.

Three times a charm. And how. My third e-book reading experiment was to read Ten Thousand Miles by Freight Train by Carrot Quinn who I'd known through her blog and mutual friends for years, but have never met. She's an excellent writer of the Annie Dillard school, and her prose has come a long way since she first started telling her train hopping tales on the internets. Her recent post about How to Be Poor is the most wonderful thing I've read on the subject in a long, long time. (Maybe ever? My memory is not whole enough to say for sure. If you are thinking about quitting your job, this is on the syllabus.)

Three times a charm. And how. My third e-book reading experiment was to read Ten Thousand Miles by Freight Train by Carrot Quinn who I'd known through her blog and mutual friends for years, but have never met. She's an excellent writer of the Annie Dillard school, and her prose has come a long way since she first started telling her train hopping tales on the internets. Her recent post about How to Be Poor is the most wonderful thing I've read on the subject in a long, long time. (Maybe ever? My memory is not whole enough to say for sure. If you are thinking about quitting your job, this is on the syllabus.)The main downside to e-booking so far, has come at review time. I enjoy reading on my phone. I enjoy the convenience of always having a couple of books with me, but I haven't gotten the hang of marking passages yet. This, in combination with the format, means that, come review time, I can't sit down to thumb through it again, letting my eyes find passages of interest a second time, helping me sum up the experience in words. Scrolling just doesn't do it for me, and my eyes are less likely to stick somewhere relevant on a screen. But! The find feature! Because of the find feature I can share my favorite metaphor—and Carrot is quite good with metaphors—in the entire book, can give you a tasty little morsel to get you ready for a delectable meal.

Carrot is describing hitch hiking, and the way that the people who pick you up tend to spill their life stories. Why do they do this? "Talking to you is like stuffing a note into a bottle and tossing it into the sea." Brilliant.

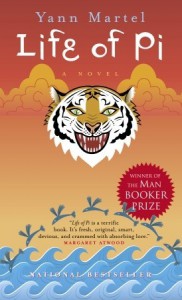

This is not the sort of story I usually gravitate to. In fact, I had been actively avoiding reading this book for some time. But then my favorite book review podcast (Literary Disco) read it, and in the same week, a neighbor bought me a copy. So read it I did.

This is not the sort of story I usually gravitate to. In fact, I had been actively avoiding reading this book for some time. But then my favorite book review podcast (Literary Disco) read it, and in the same week, a neighbor bought me a copy. So read it I did.I took me almost 200 pages to begin to see a reason to keep reading. Once Pi is on the boat, however, I started to find the story compelling. Still, I didn't see anything particularly special about this book. Then comes the end. I won't spoil it for you, but the end changes everything. "Oh," I thought, "maybe this book is worth a damn." I hadn't completely thought out the ramifications of the ending when I listened to Literary Disco's episode about the book. They took me the rest of the way. While I am not in love with this book, I finally came around in the end: it is quite a well-wrought work of fiction. About story telling, about animals, about humans. So, in the end, I was surprised to find I had almost enjoyed it.

1

1

I undertook my second e-book experiment when Tara Burns published Whore Diaries. (And I now think much more highly of e-books, tell you what.) I have loved reading her subscription blog for years—she is a great writer and she has a hell of a story to tell—and I can say the same of her first e-book. Her take on escorting is philosophical and unorthodox. The Tao of Tara. She begins with "Conversations With God in the Titty Bar," and ends far, far too soon. Write a longer book next time, huh Tara? Then again, business master mind that she is, she might just prepping readers for the longer book to come. I certainly hope so.

I undertook my second e-book experiment when Tara Burns published Whore Diaries. (And I now think much more highly of e-books, tell you what.) I have loved reading her subscription blog for years—she is a great writer and she has a hell of a story to tell—and I can say the same of her first e-book. Her take on escorting is philosophical and unorthodox. The Tao of Tara. She begins with "Conversations With God in the Titty Bar," and ends far, far too soon. Write a longer book next time, huh Tara? Then again, business master mind that she is, she might just prepping readers for the longer book to come. I certainly hope so.

I undertook my second e-book experiment when Tara Burns published Whore Diaries. (And I now think much more highly of e-books, tell you what.) I have loved reading her subscription blog for years—she is a great writer and she has a hell of a story to tell—and I can say the same of her first e-book. Her take on escorting is philosophical and unorthodox. The Tao of Tara. She begins with "Conversations With God in the Titty Bar," and ends far, far too soon. Write a longer book next time, huh Tara? Then again, business master mind that she is, she might just prepping readers for the longer book to come. I certainly hope so.

I undertook my second e-book experiment when Tara Burns published Whore Diaries. (And I now think much more highly of e-books, tell you what.) I have loved reading her subscription blog for years—she is a great writer and she has a hell of a story to tell—and I can say the same of her first e-book. Her take on escorting is philosophical and unorthodox. The Tao of Tara. She begins with "Conversations With God in the Titty Bar," and ends far, far too soon. Write a longer book next time, huh Tara? Then again, business master mind that she is, she might just prepping readers for the longer book to come. I certainly hope so.

I am totally addicted to this story, so I enjoyed reading this, but it was some of Stirling's sloppiest writing work yet. Everything about the Dies the Fire trilogy that was annoying (writing style wise) was all over the place here. For example, there was a whole lot of skipping over important scenes entirely (we watch the characters prepare and then suddenly they are talking about how it is over). As the characters are traveling cross country, however, you get a glimpse of what is going on in the rest of the country which is quite fascinating. I'd recommend it to fans, but if you didn't get into Dies the Fire, then don't bother.

I am totally addicted to this story, so I enjoyed reading this, but it was some of Stirling's sloppiest writing work yet. Everything about the Dies the Fire trilogy that was annoying (writing style wise) was all over the place here. For example, there was a whole lot of skipping over important scenes entirely (we watch the characters prepare and then suddenly they are talking about how it is over). As the characters are traveling cross country, however, you get a glimpse of what is going on in the rest of the country which is quite fascinating. I'd recommend it to fans, but if you didn't get into Dies the Fire, then don't bother.